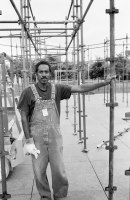

As a Walker artist-in-residence, Nari Ward held storytelling workshops over the course of six months with people from several different Twin Cities communities and asked them to describe “home.” The answers he received—from Hmong immigrants, African American and Korean seniors, homeless teenagers, college students, and local writers, among others—wove stories of memory, dislocation, community, and ritual. Ward assembled these tales against the backdrop of his detailed research into local history and customs. He was especially fascinated with Minnesota’s ice-fishing “villages,” the grand ice palaces of the early twentieth century, and the old Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul that was bisected by highway construction in the late 1950s. Lastly, he was drawn to the life and work of Clarence Wigington (1883–1967), an African American municipal architect and designer of several ice palaces in the 1930s and 1940s who had ties to Rondo.

Ward pulled all these disparate elements together in a beautifully evocative sculpture, Rites-of-Way (2000), which stood in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden for two years. During his community visits, he asked attendees to donate an object that meant “home” to them. These items—ranging from clothing, record albums, and toys to banknotes, kitchen utensils, and a slice of a sacred bur oak tree—were then ceremoniously wrapped and mailed to no-longer-existing Rondo addresses. This gesture made references to a post office in Wigington’s 1940 ice palace, the building on which the artist based his sculpture’s floor plan. . . .

Ward pulled all these disparate elements together in a beautifully evocative sculpture, Rites-of-Way (2000), which stood in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden for two years. During his community visits, he asked attendees to donate an object that meant “home” to them. These items—ranging from clothing, record albums, and toys to banknotes, kitchen utensils, and a slice of a sacred bur oak tree—were then ceremoniously wrapped and mailed to no-longer-existing Rondo addresses. This gesture made references to a post office in Wigington’s 1940 ice palace, the building on which the artist based his sculpture’s floor plan. . . .

Artist's Statement

“Through my artwork, I transform the everyday object—baby strollers, marbles, bottles, mattress springs—into visual markers. The use of all these ordinary things is about visually seducing somebody to a place they're not accustomed to being on a normal basis.”– Nari Ward